The practice of singing religious verse to popular ballad tunes was prevalent enough in England in the mid-16th century that George Wither condemned it:

The practice of singing religious verse to popular ballad tunes was prevalent enough in England in the mid-16th century that George Wither condemned it:

"For so impudent and irreligious are many in these Times growne, that I have heard in foolish and ridiculous Ballads (whose makers and publishers deserve a whipping) the name of our blessed Saviour, invocated and sung to those roguish tunes, which have formerly served for profane jiggs; An impiety odious to a good Christian; and yet use hath made it so familiar that we can now heare it, and scarce take notice that there is ought evill therein."

That the practice would continue among the American colonists goes without saying. In fact Cotton Mather suggested that since the people were so fond of ballad singing, it could be put to good use as a means of religious instruction. He was concerned that the minds and manners of many people had been "corrupted by the foolish airs and ballads which the Hawkers and Peddlers carry into all parts of the country." His solution was to "procure poeticall composures full of Piety, and such as may have a tendency to cause Truth and Goodness to be published and scattered into all corners of the land." (quotes by Wither and Cotton are taken from Christ-Janer, Hughes, and Smith, American Hymns Old and New, Vol. I. Columbia University Press, 1985) It appears that people found their own "composures full of Piety" to be sung to familiar ballad tunes in the familiar metrical Psalms and in Watts and eventually Newton and others as they emerged.

Folk Hymns

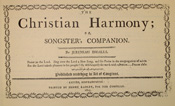

The result of this spontaneous (or sometimes purposeful) pairing of religious text with a folk melody was the accumulation of a large body of folk hymns. Folk hymnody remained an oral tradition until the hymns began to be published in singing school tunebooks like Jeremiah Ingalls The Christian Harmony, 1805 and John Wyeth's Repository of Sacred Music, Part Second, 1813. Perhaps the reason that these tunebooks (and others like The Southern Harmony, 1835; The Sacred Harp, 1844) were so popular was that they contained harmonizations of familiar tunes or brought out new tunes in the familiar folk style. In some cases we have been able to trace their melodic origins. WONDROUS LOVE, for instance, appears to be a variant of a familiar dance tune that was set to the text of "Captain Kid." SAW YE MY SAVIOR (See CRUCIFIXION in Southern Harmony, p. 25) is an adaptation of the folk song "Saw Ye My Johnny." By the time folk hymns were publish, however, their "crude" harmonizations and "jigging" melodies were beginning to be shunned by the "better music boys" (as George Pullen Jackson called them) of reform who surfaced early in the 19th century. Folk hymns survived in their original published form because they were carried by singing-school teachers and pioneers to the Upland South and the western frontier where they have been sung to this day.

The result of this spontaneous (or sometimes purposeful) pairing of religious text with a folk melody was the accumulation of a large body of folk hymns. Folk hymnody remained an oral tradition until the hymns began to be published in singing school tunebooks like Jeremiah Ingalls The Christian Harmony, 1805 and John Wyeth's Repository of Sacred Music, Part Second, 1813. Perhaps the reason that these tunebooks (and others like The Southern Harmony, 1835; The Sacred Harp, 1844) were so popular was that they contained harmonizations of familiar tunes or brought out new tunes in the familiar folk style. In some cases we have been able to trace their melodic origins. WONDROUS LOVE, for instance, appears to be a variant of a familiar dance tune that was set to the text of "Captain Kid." SAW YE MY SAVIOR (See CRUCIFIXION in Southern Harmony, p. 25) is an adaptation of the folk song "Saw Ye My Johnny." By the time folk hymns were publish, however, their "crude" harmonizations and "jigging" melodies were beginning to be shunned by the "better music boys" (as George Pullen Jackson called them) of reform who surfaced early in the 19th century. Folk hymns survived in their original published form because they were carried by singing-school teachers and pioneers to the Upland South and the western frontier where they have been sung to this day.

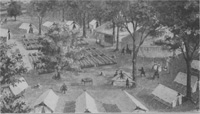

Campmeeting Songs

George Pullen Jackson suggests that while folk hymns (he called them white spirituals) have their English origins, campmeetings songs are the most American of American religious folk song. (Another Sheaf of White Spirituals, University of Florida Press, 1952) While white spirituals (like KEDRON) were no doubt used by campmeeting preachers to bring home the point of a sermon, the needs of the campmeeting revival (the first one was in Kentucky, 1801) spawned a special kind of religious folk song. Imagine the preacher reaching the end of an impassioned sermon calling the people to salvation in Christ. He could break into the song COME TO JESUS, each verse adding a new reason to make a commitment, verses like "He will save you" or "Jesus love you," and the people could chime in with ease.

Campmeeting songs were simple, often repetitive, and typically had a refrain attached. Although words-only "Songsters" were printed for campmeetings, the effective use of song depended on spontaneity and ease of singing. Some campmeeting songs took the hymns of Watts and interrupted lines with a repeated phrase (refrain) as in THE OTHER SIDE OF JORDAN. This form lent itself to call and response. The leader would sing the more complicated words of the hymn and the people would join on the refrain. In some songs they simply had to fill in a "family word:" "Say brothers (mothers, sisters), will you meet us." In others a chorus of "glory, halleluia" or "we're on our journey home" were added to the verses of a hymn as in HALLELUJAH. The simple chorus to William Bradbury's JESUS LOVES ME comes right out of the campmeeting style with its aaab form:

Campmeeting songs were simple, often repetitive, and typically had a refrain attached. Although words-only "Songsters" were printed for campmeetings, the effective use of song depended on spontaneity and ease of singing. Some campmeeting songs took the hymns of Watts and interrupted lines with a repeated phrase (refrain) as in THE OTHER SIDE OF JORDAN. This form lent itself to call and response. The leader would sing the more complicated words of the hymn and the people would join on the refrain. In some songs they simply had to fill in a "family word:" "Say brothers (mothers, sisters), will you meet us." In others a chorus of "glory, halleluia" or "we're on our journey home" were added to the verses of a hymn as in HALLELUJAH. The simple chorus to William Bradbury's JESUS LOVES ME comes right out of the campmeeting style with its aaab form:

Yes, Jesus loves me,

Yes, Jesus loves me,

Yes, Jesus loves me,

The Bible tells me so.

For an excellent discussion of campmeeting songs see Ellen Jane Lorenz. Glory, Hallelujah! Abingdon, 1980.